Piecing himself together from fragments of memory: a Ukrainian war reporter recovers after being wounded

He lost the memory of his daughter's birth, but he will never forget Russia's crimes against Ukraine. Ivan Liubysh-Kirdei, a Reuters war correspondent and winner of the George Gongadze Prize, was seriously wounded in the head during a missile attack on Kramatorsk in 2024. Almost a year later, he is reconstructing his life from the stories of his loved ones and the few memories that remain after his injury. Without self-pity and with a will to fight, the journalist works every day to restore his body and return to work. Today, as before, Ivan strives to document Russian aggression and reveal the truth about it to the world.

Ivan Liubysh-Kirdei is a Ukrainian photographer, cameraman, and, since 2022, a war correspondent for Reuters. He has extensive experience in media, having collaborated with Ukrainian and international publications, including 1+1, Current Time (a Radio Svoboda/Radio Free Europe project), and the German television channel ARD.

In 2013, Ivan covered the events of the Revolution of Dignity, and later, Russia’s annexation of Crimea. With the start of the war in 2014, he went to Donetsk Oblast. In August of that year, together with journalists Maks Levin, Heorhii Tykhyi, and Markiian Lyseiko, he found himself in the Ilovaisk cauldron, the encirclement of Ukrainian forces near the town of Ilovaisk. The film “Bloody War in Ukraine – Escape from Ilovaisk,” shot by Liubysh-Kirdei, was nominated for the title of Best Television Documentary at the Monte Carlo Television Festival. In 2015, Ivan won the Deutscher Kamerapreis award for his cinematography.

During the full-scale Russian invasion, Ivan continued to work on the front line. In August 2024, together with a Reuters team, he documented the evacuation from Pokrovsk, a city that had become the hottest spot on the front line and the main direction of the Russian offensive. The last report Ivan filed from Pokrovsk was published on Aug. 22, 2024.

Two days later, on Aug. 24, the journalists returned from filming and checked into the Sapfir Hotel in Kramatorsk. At night, the Russian army struck it with a high‑precision Iskander‑M ballistic missile. Reuters security adviser Ryan Evans was killed in the attack, and Ivan was taken to a hospital in critical condition with a severe head wound and other injuries. The journalist was in a coma for more than a month. Doctors told his loved ones to believe for the best but prepare for the worst.

Memory loss

Ivan regained consciousness in early October 2024, his wife, Mariia Semenchenko, wrote on Facebook.

“The first thing he said to the doctors was some advice on what to do with our neighbors, you know who. Well, because Ukrainians come out of comas with words like that,” Mariia wrote at the time.

So Ivan remembered that there was a war in Ukraine and understood well “what Russia is.” He recognized his relatives, colleagues, and acquaintances but could not recall the moments he had shared with them. As Mariia wrote at the time, Ivan could remember different details — such as the lyrics of his favorite songs — and yet forget how old he was or that he was married.

Almost a year later, he is still piecing together memories of his life from what other people tell him. Family, friends, and colleagues recount where he was and what he saw, but he himself cannot remember even the birth of his daughter.

“I remember, as if in a fog, only how they brought her to me and laid her on my chest. And what happened next — how we came home, what those first days were like — I don’t remember anything,” Ivan says.

Today, even Kyiv, the city where he has lived for 22 years, looks like a new place to him. Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square), where Berkut riot police smashed his camera during Euromaidan, also seems unfamiliar.

“Have you ever been abroad? That’s what it feels like to me, as if I am in another country,” he says.

Ivan admits that living without memories is exhausting, but he does not try to force them back. His rehabilitation specialist reminds him not to be too critical of himself and to give himself time — his memory will gradually return. Ivan accepts this without regret and, instead of clinging to the past, works every day to restore his body.

“I live for today and tomorrow. If I don’t work hard today, tomorrow will be bad for me. That’s why I constantly tell myself: Vanechka, go hard,” he says.

Memories of a war correspondent

For the first time since being wounded, Ivan scrolls through his photos on Instagram. Mostly landscapes and portraits of loved ones. Still, he cannot recall where and under what circumstances he took them. Suddenly, he stops at a photo of a pier on the sea — he recognizes this image.

“We took this in occupied Crimea,” he says.

However, a moment later, he notices the caption under the photo: “Odesa, 2018.”

Among the photos is the Derzhprom (State Industry Building) on Kharkiv’s main square, which Ivan also does not recognize now. When asked what he associates Kharkiv with, he smiles and answers simply, as if it were obvious: “With Zhadan!” He and his daughter are big fans of the band Zhadan i Sobaky (Zhadan and the Dogs). Serhii Zhadan is a celebrated Ukrainian writer and musician from Kharkiv, as well as the band’s frontman.

Then the journalist recalls another detail about the front-line city.

“In the Kharkiv Oblast, I remember filming in Izium, where there were mass graves. I remembered this when I smelled the musty air. I remembered that there was sand and forest, and they were pulling bodies out of the sand… I filmed huge piles of corpses. And there was one photographer who picked mushrooms in that forest. I just remembered that,” says Ivan.

Looking through the reports he filmed for Reuters, Ivan shakes his head — he remembers almost nothing. However, some of the footage brings back memories.

“It was in Bakhmut. We were filming mortar fire and a tank firing from a covered position. We didn’t film that because it was being hit,” he recalls.

Although his memory is still fragmented, Ivan remembers well what is tied to the work. He can clearly identify different types of weapons; he remembers how to construct a frame and composition; he knows how to operate a camera and the Adobe Premiere editing program; and he hasn’t forgotten his English. He now applies his skills to help the Tytanovi (Titatium) Center in Kyiv, where he is undergoing rehabilitation and where wounded service members are also treated. There, he shoots photos and edits videos from training sessions and procedures, similar in style to the reports he made for Reuters.

Rehabilitation

Leaning on a cane, Ivan walks into Tytanovi’s gym. He says he trains every day to return to work as quickly as possible. To be able to hold a TV camera, he works to recover his injured arm and constantly squeezes a hand‑grip exerciser.

Suddenly, Ivan turns and leans closer, pointing to his eye.

“You see, I recently had an implant inserted. It’s temporary, but it’s good because now I won’t scare children,” he says.

His 9‑year‑old daughter Oleksandra was never afraid and boldly kisses her father on both cheeks. Recently they performed together at a Zhadan i Sobaky concert — it was their dream. Ivan played the bayan, while Oleksandra sang with Zhadan.

Like her father, the girl loves music, plays the bayan (button accordion) and guitar, and knows Zhadan’s songs by heart. Her favorite is “Tyolka barabanshchyka” (“The Drummer’s Girl”): because tyolka is a slang word for “girl,” she mishears it as cholka, which means “bangs” (fringe), and sings it that way. “She doesn’t know the word ‘tyolka’ yet, so she sings ‘cholka.’ It’s just hilarious,” Ivan laughs.

He explained to his daughter that their performance was not just a concert but a way to raise money for the army. She replied that she was ready to sing every day, so long as the money helps the military.

“We don’t teach her this — she wants to help the army herself,” Ivan says.

Music also helps Ivan with his rehabilitation. Although he cannot yet play as masterfully as before, playing the accordion helps restore his motor skills. At the same time, Ivan entertains and supports the soldiers who are also undergoing rehabilitation at Tytanovi. Every day at 9 a.m., after a minute of silence, Ivan plays the Ukrainian national anthem for them.

Return to the front line

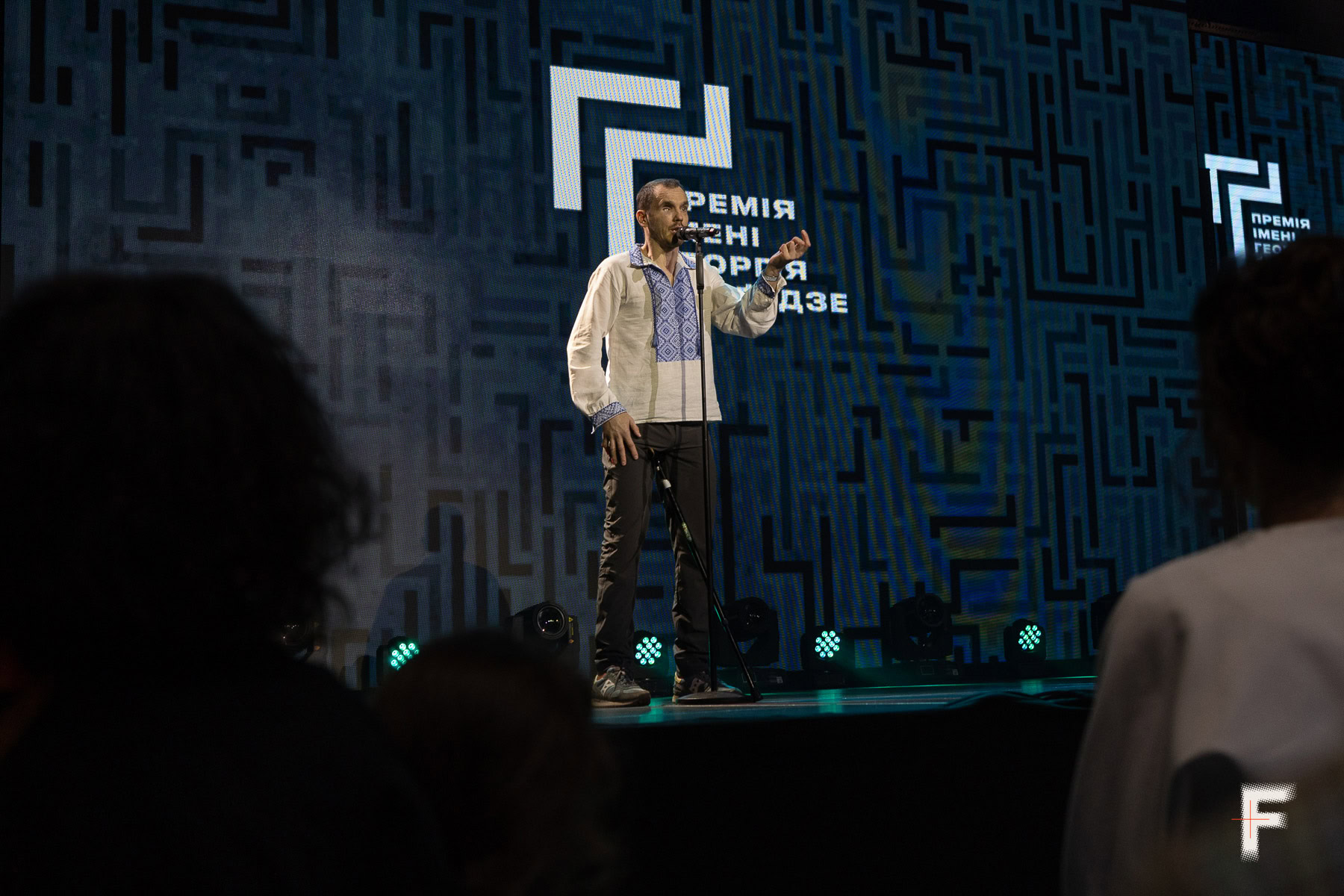

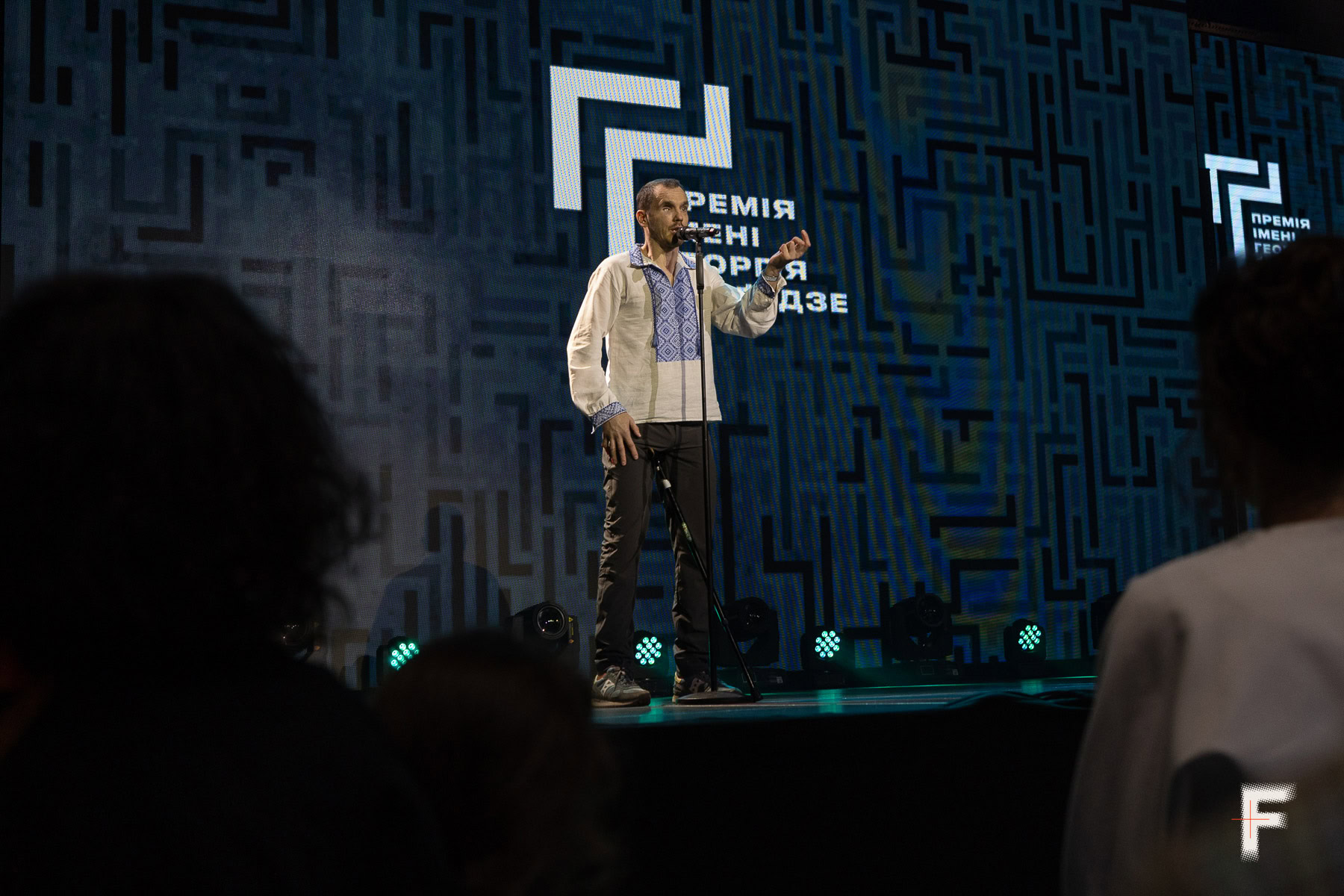

In May 2025, Ivan Liubysh‑Kirdei became a laureate of the George Gongadze Prize. When he learned of the nomination, at first, he did not remember what prize it was, so he had to look it up online. When he learned more, he was struck to find himself alongside prominent Ukrainian journalists.

Ivan says the award gives him motivation not to give up, neither as a person nor as a professional. Although he would prefer the war to end before he fully recovers, as long as it continues, he must work to show the world the truth about Russia’s war of imperial conquest. The journalist states without hesitation: despite the danger and risks, once he has recovered, he will return to the front line.

Text: Viktoriia Kalimbet

Photos: Danylo Dubchak; archive of Ivan Liubysh-Kirdei

Adapted: Jared Goyette

Read more — The murder of Viktoriia Roshchyna shows: The Kremlin is losing control over its torturers