Names that wait: how Ukraine identifies the fallen

Ukraine is bringing home her fallen defenders. But with each body comes a difficult undertaking: determining their identities. Identification of the dead has become one of the most challenging tasks of the war, requiring modern equipment, patience, and the psychological resilience to face the consequences of war every day. The bodies often arrive broken and entangled, demanding the utmost precision and care at every step. It is through this difficult work that human dignity is preserved. Frontliner tells how the fallen are given back their names – and how their families are given the chance to say goodbye.

The identification procedure involves several stages: examination and documentation of the body’s condition, cataloguing of personal belongings, collection of biological samples, laboratory analysis, and the search for DNA matches. To the public, these steps are nearly invisible – but to families, they mean everything: confirmation of the fate of their loved ones and the chance to bury them with dignity.

Forensic experts, criminologists, and attendants work under difficult conditions. Many of the returned bodies are in advanced stages of decomposition – mummified, charred, or decomposed. A few years ago, Ukraine’s system was not ready for the scale of such work, but today it has developed its own solutions: from mobile field morgues and streamlined DNA queues to the pioneering of a unique necrodactyloscopy method.

This experience is crucial not only for families who seek news of their loved ones but also for the world, offering lessons on setting new international standards and adapting DVI (Disaster Victim Identification) systems to the realities of war.

The first step of identification

The field morgue, organized this spring to improve logistics, is located right next to the refrigerated train cars where bodies are stored. The arrival of each repatriation marks the moment work begins. People in protective suits unload the train cars and carry the white body bags to tables inside a large tent. Anything could be inside each bag.

“We never know what exactly is in the package,” says Tetiana Papizh, head of the Odesa Regional Bureau of Forensic Medical Examination. “It might be a body, or it might be fragments, for example four feet belonging to different people.”

The bodies are distributed on autopsy tables. Each body goes through the same procedure: photographing, noting identifying features, searching for documents or belongings, and, if possible, taking fingerprints. A forensic pathologist determines the cause of death while an investigator records everything in the official report.

Every body receives a unique 17-digit identification number, encoding everything – the date of arrival, the facility that received the body, and sequence number. It becomes their new name until the real one is restored.

“We carried out the first seven repatriations right in the morgue,” recalls forensic pathologist Viktor Mahrinchuk. “Starting from the eighth, we’ve been working here, in the field laboratory. In the morgue, we could process one or two bodies a day, three at most, because we spent the first half of the day doing our main work and only then moved on to repatriation. Besides, we had to wait for the investigative team, and there weren’t enough tables in the morgue.”

Now, the scale is completely different: experts can process about a hundred bodies per day.

We are the first in Ukraine to organize such a process.

Decomposition, charring, mummification – some bodies had lain for a year and a half, two years, or even longer. In such conditions, visual identification is nearly impossible. Yet investigators meticulously document every detail, from shoelaces to tattoos, even when they are partially destroyed. Sometimes a piece of fabric, a set of keys, a wedding ring, or a military tag becomes the clue that helps narrow the search. If such items are found, they are photographed, described, packed separately, and returned to the bag with the body. Personal belongings of the fallen, if preserved, are important but not decisive. They cannot replace genetic analysis, yet sometimes they bring closer the moment when an anonymous entry in an official report turns into a name.

Storage conditions and the scope of the work

Tetiana Papizh often makes time to “go into the field” to help the team. The workload is immense: in the summer alone, Odesa received 1,600 bodies. In total, since early May 2024, eleven repatriations have taken place – more than 2,800 bodies.

These are the bodies of Ukrainian soldiers returned from Russia through prisoner exchanges. Since the beginning of the full-scale war, the largest repatriation brought in 6,000 bodies, with Odesa receiving nearly a third.

The bodies are stored in refrigerated train cars, where the temperature remains stable at -10 degrees Celsius. This is a temporary storage site while identification is underway. If a person’s identity cannot be determined within a year, and all laboratory tests are complete, the body is buried with full honors in a specially designated area. It will remain there until a match is found with relatives in the DNA database.

This is our mission, and it is our duty to fulfill it.

At each autopsy table, a team consisting of a forensic pathologist, a laboratory technician, an orderly, an investigator, an operations officer, and a forensic investigator work. There are eight tables, with six people at each. Specialists from the State Emergency Service (SESU) and the State Scientific Research Forensic Center (SSRFC) of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, as well as explosives experts, are also present onsite. In total, there are nearly one hundred professionals involved.

“It was especially difficult in the summer,” recalls Papizh. “People were exhausted; we asked for air conditioners, water, and portable toilets. But no one walked away from the work.”

Obtaining a DNA profile takes 14 to 21 days depending on the material, be it muscle tissue, bone, or cartilage. The results are sent to a central registry, where they are matched with the DNA profiles of missing persons’ relatives.

The system is constantly improving. Mistakes do happen, specialists admit, but each repatriation is more organized than the last. Ukraine is developing a practice it has never had before: the mass identification of those killed in war.

When DNA becomes the only witness

Work moves from the field morgue to the laboratory. This is the second stage of identification, unseen by most, yet crucial. In specially equipped facilities, genetic experts work with coded packages. There are no names, no stories – only the biomaterial and official information such as body number, date, region.

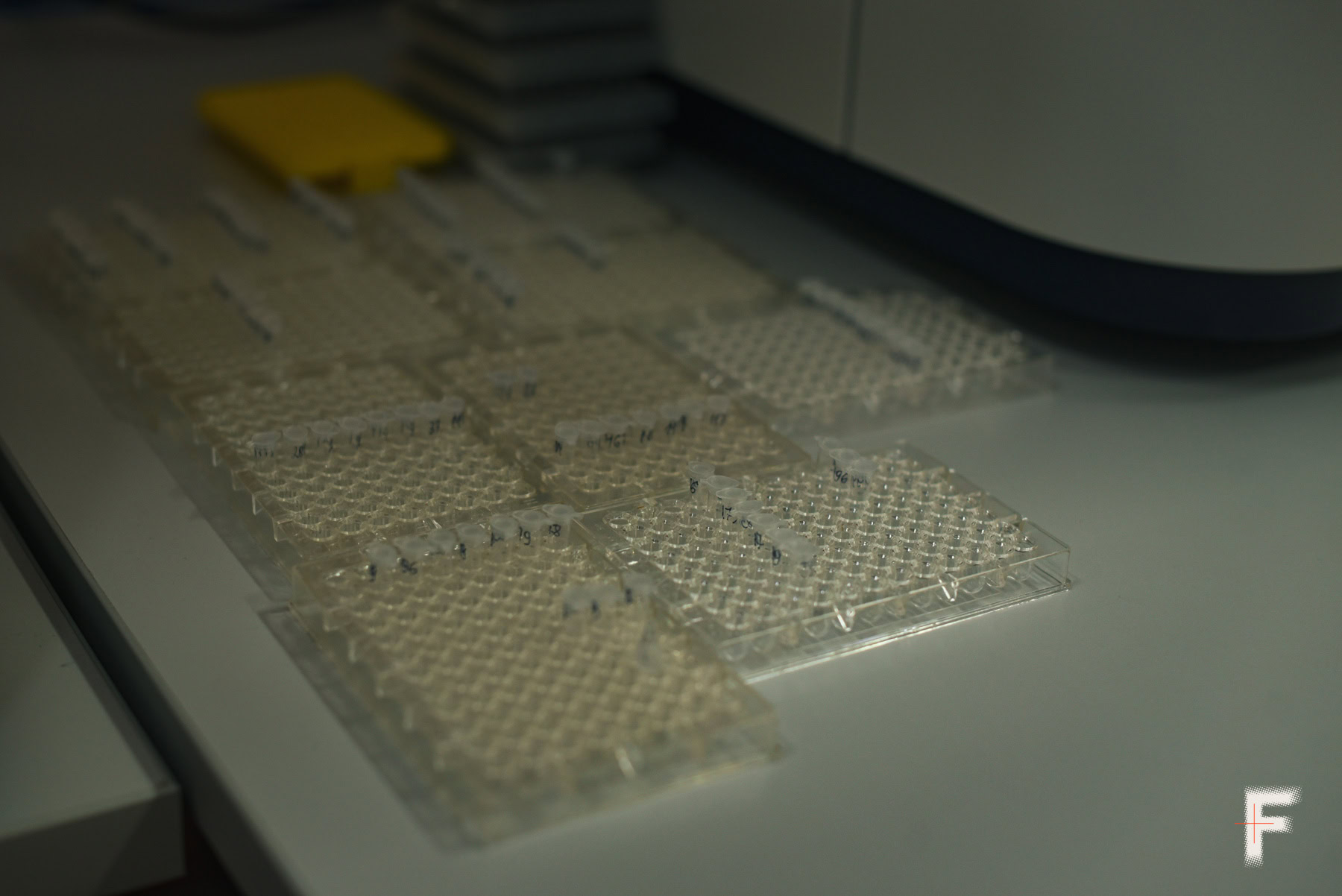

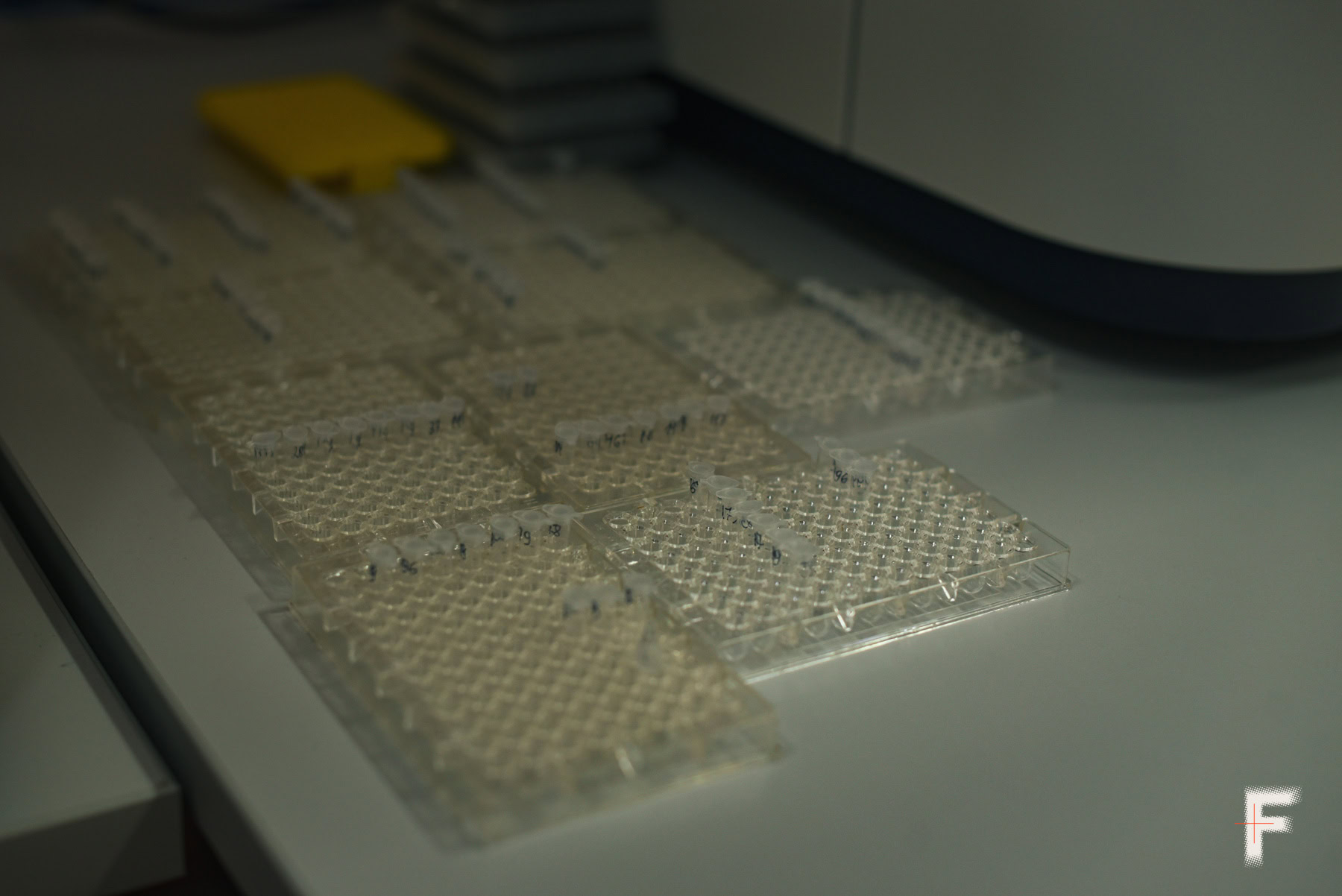

In the evidence processing room, everything is impeccably clean and orderly. This is where evidence is examined and made ready for analysis. On the tables lie bone fragments, test tubes, and containers. Ruslan Kryvda, Head of the Molecular Genetic Examination Department, carefully opens the package and shows the prepared material.

“The package arrives from the site with the corresponding documents. This is how it comes to us. We follow the methodological guidelines of the European Committee of Forensic Experts, which specify exactly what needs to be collected. Depending on the condition of the body, we take biological samples. Here, we collected two clavicles, the sternum (which already has a number; we have analyzed it), and the cervical section with the first vertebra,” he explains, pointing to the fragments.

On a table nearby lies a pelvic bone. “There was no cartilage or muscle tissue – this is a skeletonized body, with a time of death over 12 months. We took the first vertebra, mechanically cleaned it, and collected a fragment of the arch. For this, we use a level 3 or 4 biohazard container, which safeguards the researcher from pathogens, such as tuberculosis.”

From bone to digital profile

Analysis usually relies on the jaw, clavicle, rib, or patella, which provide quicker results.The samples are cleaned before any DNA is extracted.Teeth or bone fragments are ground into powder, and this material is transferred into a test tube for further DNA extraction.

All DNA profiles are analyzed across 24 loci (a specific region of a chromosome where a particular gene or another unique DNA segment is located – essentially an “address” within the genetic code). Specialists use these “addresses” to compare DNA from different individuals, determining whether they are related or whether the samples belong to the same person, adhering to international standards to ensure precise matches. The data is entered into the Unified Human Genomic Information Registry created by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which holds thousands of DNA profiles of relatives of missing persons.

As a crucial first step, the DNA is evaluated for quality and quantity, and then stabilized to avoid the unnecessary use of costly materials. If the DNA is degraded or the material is unsuitable, experts can request new samples, requiring fragments to be collected again. Temperature, storage conditions, and time since death all affect the outcome. Even the smallest detail can complicate the work – a fragment mixed with another body or traces of soil can hinder the isolation of clean DNA. Unfortunately, most remains repatriated from Russia arrive in very poor condition.

In this work, the equipment is just as important as the hands that operate it. Thanks to the support of donors and partners, experts have access to modern molecular-genetic analyzers, expensive reagents, consumables, and other tools that facilitate the work of field teams and accelerate laboratory examinations.

“This is a Genetic Analyzer 3500, a fully automated station, calibrated down to the millimeter. It automatically produces an accurate profile,” says Ruslan Kryvda. Then he points to an older machine sitting off to the side. “This one had been in use since 2007, before we received modern devices.”

Training on new methods and equipment is just as important, and is also supported by donors and partners.

How Ukraine is developing new methods

Identification work does not end in the laboratories. In addition to their daily work, experts are increasingly focusing on training, knowledge exchange, and developing new methods to identify names faster and more precisely

This work is overseen by the Romulus T. Weatherman Foundation, an international humanitarian organization that helps Ukrainian specialists locate, identify, and repatriate fallen foreign volunteers. The foundation coordinates the search and transportation of bodies home, assists in creating a unified system of standardized identification, supports forensic institutions, and trains experts in new techniques. The foundation also implements innovative approaches, including necrodactyloscopy, developed by Ukrainian forensic experts in Vinnytsia. This method allows fingerprint recovery even in the most extreme cases: after charring, mummification, or decomposition.

According to Iryna Khoroshaieva, Director of the Warfare Victim Identification program, which coordinates the search and repatriation of missing foreign volunteers, the foundation’s work goes beyond technical scope. Its team supports the families of the fallen and missing, assisting with at-home DNA sample collection, legal procedures, documentation, and court rulings. For the families of deceased foreign volunteers, this is very important because only an official confirmation of death allows a service member’s status to be changed, a death certificate to be issued, and tax obligations to be terminated.

The mission of the foundation is to return a name to every fallen person and provide closure to families who are waiting, as well as strengthen the humanitarian response system, making Ukraine an example to the world in the dignified treatment of the dead.

When numbers turn into names

Currently, experts use the Unified Human Genomic Information Registry, created to accelerate the identification process for repatriated bodies of Ukrainian defenders and civilians killed as a result of Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine.

“We have access to the Unified Human Genomic Information Registry database at the Ministry of Internal Affairs [Editor’s note: the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine is the main executive body coordinating the search for persons missing under special circumstances], I officially requested it. Now we can immediately see when an analysis is completed, and I can call the investigator and ask to schedule a comparative examination because we see a match,” explains Papizh. This is how the process accelerates – the system constantly evolves, and the search for matches continues without pause.

The profiles of relatives who provided samples after a loved one went missing are used for comparison.

“Regarding comparative examinations, when a profile is entered into the registry the profiles of relatives are already in the system. Relatives typically provide samples after being informed that a service member is missing. When there is a match, the investigator schedules a comparative examination. We compare the DNA profile obtained from bone material with the DNA profile of the relatives. Two relatives are needed to identify the individual,” explains genetic expert Iryna Lantsman. “Most often, this is the mother and father or two relatives on the father’s side. Only then can we confirm a match.”

Once a match is found, an official conclusion is issued and the body can be released to the family. If an identity cannot be established within a year, the body is buried in a designated area under the previously issued individual number. This happens when there is no genetic material to compare – for example, if the fallen has no relatives or they are in temporarily occupied territories. A genetic profile is preserved so that, even years later, the grave marker can be updated from a number to a name. If the deceased is identified, the “On Their Shield” mission delivers the body to their family for burial.

Two years ago, the system was unprepared for such scale; today, it is setting new standards. Ukrainian experts are pushing the boundaries of possibility, devising methods the world has never seen. This experience may even form the basis of future international standard procedure.

Author: Tetiana Kreker

Adapted: Irena Zaburanna

Читайте також — Restoring the name: how Ukraine identifies its fallen and brings them home