A step toward a new life: women from prison join the war effort

Formerly incarcerated women have joined the military and are now serving on the Zaporizhzhia front. They operate attack drones, even though just a few months ago they were serving prison sentences and working in a prison sewing workshop. Frontliner followed their journey from the correctional facility to their first combat deployment and explored why they see the army as a second chance.

Three women in tactical clothing, carrying folders, walk through the prison yard. Behind the large, murky windows of the sewing workshop, the faces of other women can be seen, watching the newcomers with curiosity. As the military personnel enter, a crowd is already waiting by the door. The women are dressed in a patchwork of styles: some in rubber shoes, others in sneakers or felt boots. Their heads are covered with colorful scarves.

A gray-haired, fit man wearing rectangular glasses begins speaking to the women. This is “Jazz,” deputy commander of the First Assault Regiment for Psychological Support. He has visited dozens of correctional facilities across Ukraine, recruiting many capable assault fighters since a law was passed allowing the mobilization of convicted individuals. Today, his task is different: to invite the women to join an experimental female drone-operator company.

We want to take in trustworthy people who want

to change something in their lives,

For him, these are not only platitudes. He believes the army can truly offer a second chance – something that rarely happens for those with criminal records. “Jazz” gestures toward Oleksandra, a young woman in military uniform who arrived at the facility with him. At the end of summer 2024, she was granted early release from prison and joined the military. She quickly earned the trust of the command. Now a senior sergeant, she recruits volunteers for the battalion herself.

Five out of forty

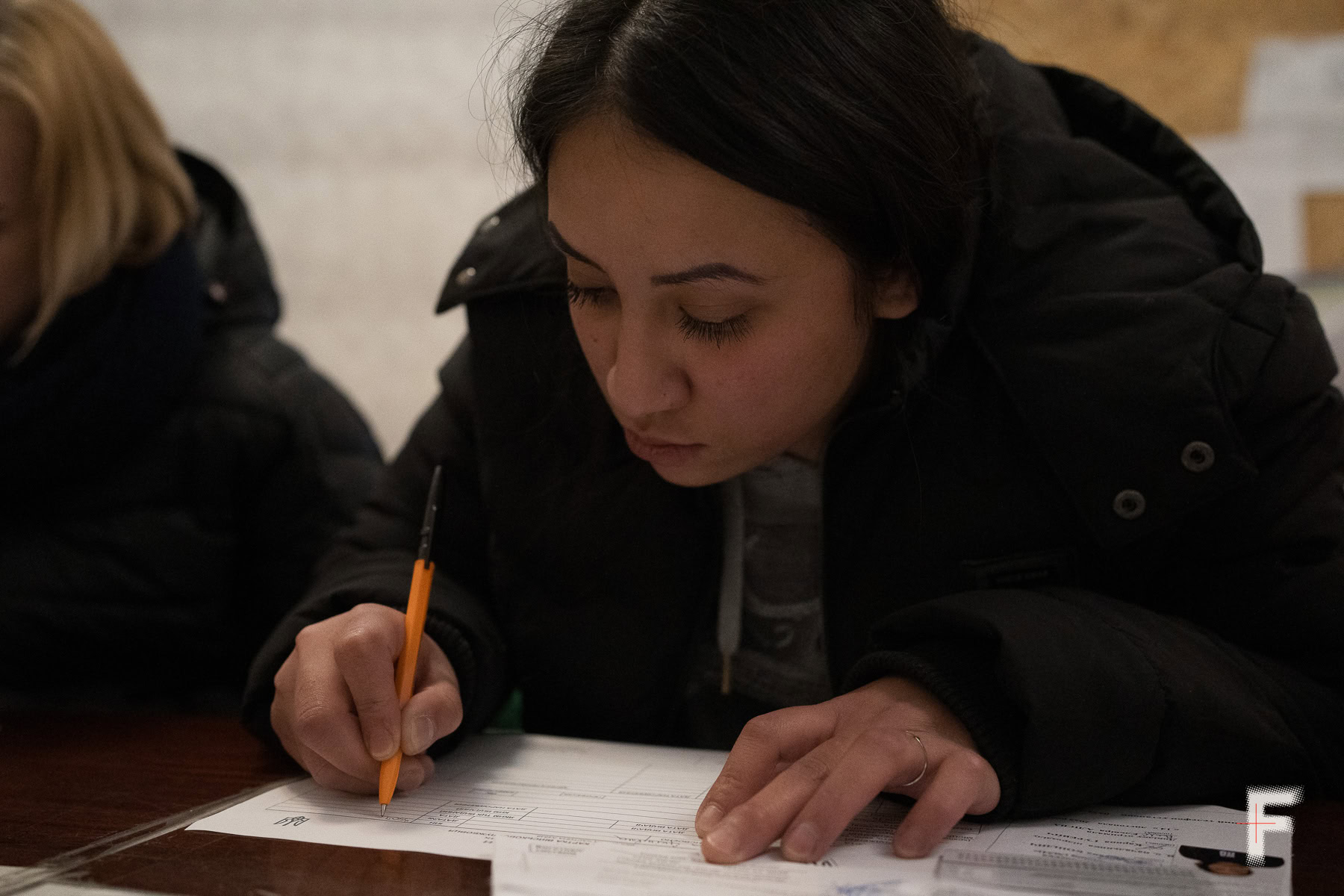

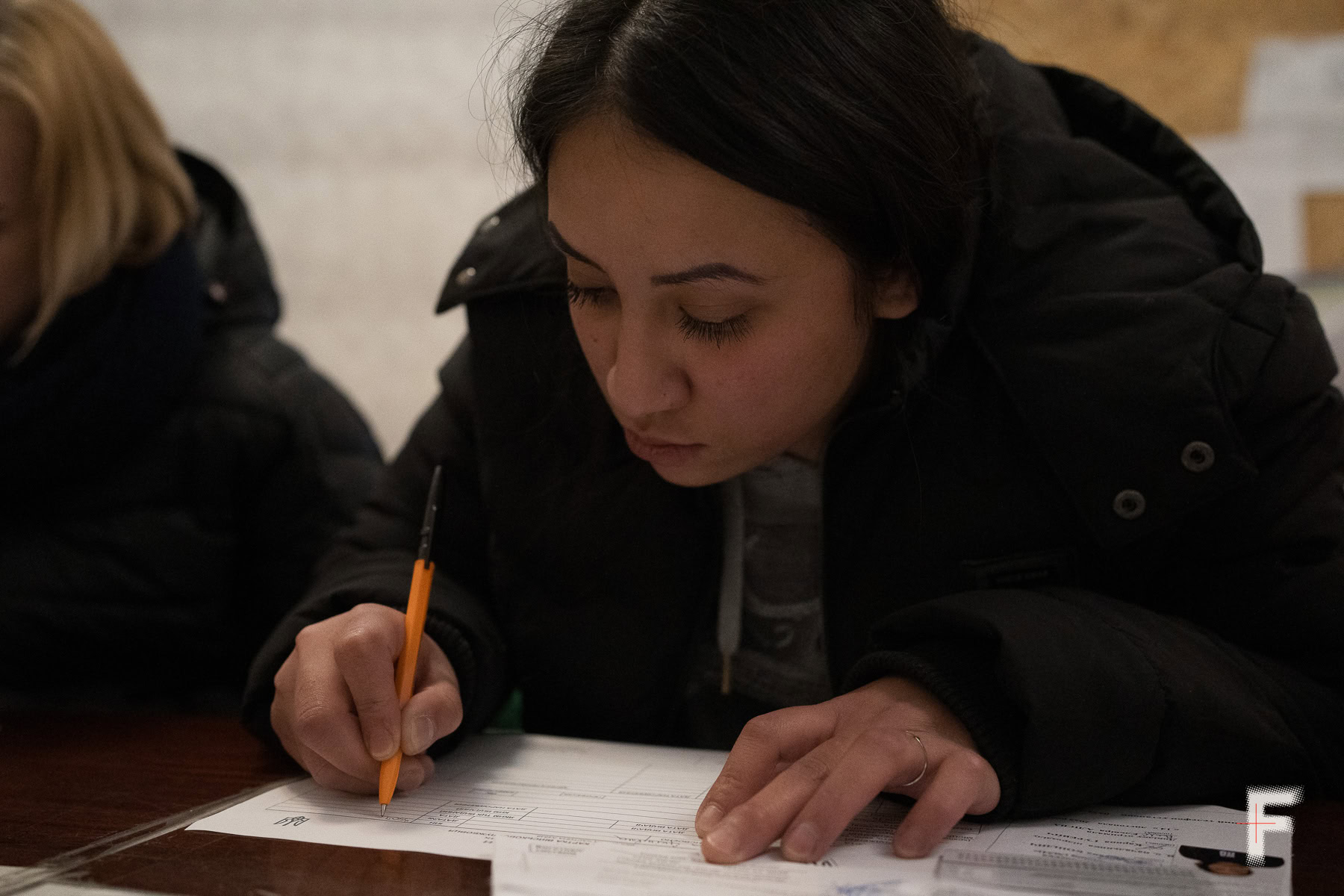

Following the address, several dozen women sign up for interviews, which are held right in the correctional facility. Some speak frankly: they have decided to follow Oleksandra’s example because they know her personally. But a strict selection process lies ahead. The 1st Assault Regiment seeks volunteers without drug or alcohol dependence. Commanders are convinced these issues “thin out” personnel faster than enemy attacks. Other requirements include being free of severe infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis or HIV.

Some women barely enter the office, and “Jazz” quickly determines they may not be ready for the program. A glance at their faces is often enough for him to recognize signs of dependence. However, he talks with most of the women to confirm whether their path aligns with the regiment.

A brunette with dark eyes enhanced with mascara and tattooed eyebrows sits at the table across from the recruiters. She cites Article 307, Part 3 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine: distribution of narcotics.

“What did you use?” “Jazz” asks without judgment.

“Methadone. Twelve years,” she says without emotion.

“Jazz” considers for a moment and replies:

“Our approach to drugs is strict. I’m being frank here in front of the administration. I’ve already sent 30 people back to their ‘alma mater’ with an extra eight years added,” he says.

“I’m not going there to distribute drugs. I won’t let you down,” the inmate assures.

“Jazz” regards these promises with skepticism. Sitting next to him is the commander of the battalion of former inmates, “Yozh,” who keeps an open notebook on his lap and silently marks a minus next to this candidate’s name. As the interviews progress, he adds more minuses, with only a few cases prompting discussion among the recruiters.

A woman with coal-black hair enters the office. She stands by the door, head lowered, and does not sit until invited. “Jazz” narrows his gray eyes, studying her face.

Twenty-nine-year-old Elvira says she is an orphan and is serving time under Article 115 – homicide. She says it happened in self-defense. She has served two years of her sentence, with five remaining. She completed only seven grades of school and continues her education in the correctional facility.

When Elvira leaves the room, the prison administrators advise the recruiters against taking her into the military saying she is currently psychologically unstable. Even so, “Jazz” sees potential.

“She has no one. I want to give this kid a chance. We’ll take her,” he says resolutely.

“Jazz” warns each volunteer that there is no turning back. If they fail, consequences will follow and they will be sent back to prison.

Over two days, the recruiters spoke with forty women and chose only five – all from the same correctional facility. Together, they will confront new challenges.

Although the recruiters had hoped for a larger number of recruits, the quality of applicants remains their primary concern. The list is then sent to state authorities, followed by a medical commission. If everything goes smoothly, the candidate proceeds to a court hearing where they can still decline to enlist.

Prison life

Formerly incarcerated women refer to the correctional facility as a “camp.” Life here is oppressive: the days drag on like weeks, the women say. Everything is monotonous – both the work and the faces around them remain the same.

“Not a day goes by in the camp without a feeling of guilt,” says 40-year-old Natalia, who has been incarcerated for two years. She was convicted under Article 185 – theft. Under martial law, sentences are harsher, and Natalia received five years. Her time in prison became a turning point – she felt she had hit rock bottom and was convinced that, because of her criminal past, she would have no future.

For me, the mobilization of convicted individuals is a step toward a new life.

I am ready to devote myself fully to this cause,

She waited for the recruiters every day and kept pressing the administration about her interest. Her decision to join the military was not spontaneous – she had thought about it for many nights, Natalia says. When the 1st Assault Regiment arrived at the facility, she went to the interview and insisted that she was determined to turn her life around. “Jazz”, however, did not believe her.

“Please think about it. One day we’ll sit at the table, and you’ll see that it was not a mistake,” Natalia assured him.

“We need to think it over,” “Yozh” replied.

Soon, Natalia learned of the decision. After two unsuccessful interviews with other units, she was accepted into the military. She had no idea where she was going; inmates are cut off from the outside world and have a limited understanding of the war. She knew nothing about the “Shkval” battalion she was being mobilized into. Yet one thought gave her comfort:

For my children, I will not be a convict mom,

but a soldier mom,

She believes that prison was only a phase, not something that defines her whole life. Now she can build a different future.

That day, Anna was released from prison. She had been imprisoned at 21, serving a sentence for homicide with a scheduled release in 2028. Anna says she killed her attacker in self-defense. Until the final court hearing, she did not believe she would be sentenced to prison. She blames poor legal representation for the outcome.

Before leaving prison, she couldn’t sleep, the young woman recalls. She lay on the bunk, listening to her own heartbeat. By morning, her anxiety had only grown – after four years inside, she had no idea what life outside would be like. But the moment she stepped through the prison gates with her bags and climbed into the military vehicle, a sense of calm washed over her.

“We had just left the prison, and I already felt as if I had never been there,” Anna recalls.

Basic training

“Jazz” managed to have Elvira accepted into the military, despite the lack of support from the prison administration. She could hardly believe it was really happening. The mobilization process moved quickly: before she had a chance to collect her thoughts, Elvira was already standing at the prison gates with her bags.

If I survive, the army will set me on the right path,

During the journey, the young woman watched cars whizz by, shop windows, and pedestrians – ordinary life in a big city. When the mobilized recruits arrived at a house in a village in Donetsk region, everything felt surreal. Then began the process of adapting and setting up daily life. The first thing the women did was buy some cosmetics. Soon, new daily responsibilities set in: monitoring the generator, carrying water from the well, stoking the stove, taking turns cleaning, and preparing meals.

Soon, another young woman arrived at the house: 24-year-old Daria. Her path in the military had not been easy. She joined during the first wave of mobilization for female inmates, but disciplinary issues led her to move from unit to unit. Daria served on the Pokrovsk front, preparing meals for her comrades and providing first aid. It was there that she learned firsthand what “medevac,” “300” and “200” meant.

[Translator’s note: In Ukrainian military terminology, “200” is a code word for killed personnel, while “300” refers to those wounded.]

Eventually, she returned to “Shkval” of the 1st Assault Regiment. Now Daria is undergoing training for the second time alongside the new recruits and is retraining as a drone operator.

The idea of serving came to her back when the mobilization of male inmates began. She was afraid, but above all she saw it as a chance to provide for her two young sons, who had been left in the care of their grandmother.

“I waited for the recruiters for a whole month. I would fall asleep thinking, ‘Please, come.’ Every day, I woke up at six in the morning and put on my makeup,” Daria recalls.

Daria, call sign “DShK,” is one of the more optimistic members of the group, constantly boosting the spirits of those around her. “Jazz” sees Natalia gradually revealing her true self as an organized and responsible person. She keeps the house in order and trains diligently at the range. She used her first paycheck to buy a tactical first-aid kit. Anna, call sign “X,” was initially reserved, but she soon immersed herself in the training. Elvira, “Niam-Niam,” is slowly opening up as well, though it is hardest for her. She admits she has sometimes regretted her decision, feeling out of place.

During the last week of training, the weather turns cold. The women go through their morning routine: packing up, grabbing coffee, and having a quick breakfast. While they put on their gear, Natalia is already lining up the benches along the kitchen table and washing dishes. Outside, an SUV waits to take them to the training ground. The women toss their body armor and backpacks into the vehicle, and some climb into the open bed. On the road, the cold wind stings their cheeks.

When the SUV arrives at the “Shkval” base, men approach the vehicle, greet them, and try to joke around. The women, however, are focused on the tasks at hand – they need to collect their weapons and sign the paperwork.

“Should we grab the ammo?” Natalia asks senior sergeant Oleksandra, call sign “San Sanych.”

“No, we’ll be shooting with f*ing pebbles,” she replies sarcastically.

Senior sergeant “San Sanych” also known as Sashka, can be sharp, but the women don’t take offense. On the contrary, they respect “San Sanych” and often express their gratitude to her and the commanders for giving them a second chance to prove themselves.

“The team we have came together thanks to one person. That’s Sashka,” Natalia says.

The SUV drops the women off near the training range. They head out to the firing line, dragging their boots through the mud. They carry heavy boxes of ammunition. Before the shooting starts, the women are nervous – they’re not hitting the target consistently yet. Daria, callsign “DShK,” cheers them up:

“It is okay girls, we’re still learning. We will f**k up the f*ers.”

First encounter with real war

For several weeks now, during the coldest part of the winter, the former female inmates have been stationed near the gray zone on the Zaporizhzhia front, waiting for their first combat sorties. There’s little time for reflection: they must manage life in extreme conditions, train, and continue their education. The volunteers’ perseverance is a welcome sight for their instructors. “Morf,” who teaches them to operate drones, says:

“I can see they’re putting in the effort. They have the motivation, so they’ll succeed. And in all these three months, not one of them has backed out of a combat mission.”

A few months ago, the women had no idea what awaited them. Anna steeled herself for the worst. Natalia knew she was taking a serious risk. Every morning, Elvira wrestled with the thought: “I don’t belong here.” Daria found motivation in the fact that she was protecting her children. And though the conditions are harsh, their time in prison had made them resilient.

In the Zaporizhzhia region, the reality of the war began to take shape. They saw the infantry soldiers off to their positions and, over the radio, heard that some of them had been wounded or killed. Later, the women themselves would go out on missions – serving as the infantry’s “eyes.”

Natalia went out first. Reaching the positions proved difficult: the Russians were firing mortars, and along the way, they kept running into waiting drones. Natalia and two comrades moved in short sprints across the exposed ground under a sky cluttered with drones. But fueled by adrenaline, Natalia barely felt the weight of her bulletproof vest and the backpack packed with all the essentials.

The soldier says that the next seven days on the front were a constant strain, a rollercoaster of tension and uncertainty. There was no time to let their guard down – the Russians kept pounding the area with mortars and drones.

“I realized there how much you have to value every single second. I reexamined my worldview and started taking life more seriously.”

Before, I was just existing – now, I’m truly breathing,

A week later, Natalia left the frontline position. Frostbite still marks her face, and her body is covered in lesions and blisters from the cold and stress. She isn’t sure if she’s ready to face the front again. But when she’s ordered back, she will go.

“I can’t say I liked being on the positions. But the door to the “camp” has cracked open, and I still have something left to do. So I want to do what I can,” she says.

She tried to prepare her friends that the front was nothing like they expected. She wanted to pass on what she had learned, even though she understood that this was, in truth, impossible. The front is unpredictable.

After Natalia, Anna was next to rotate to frontline positions. The night before her mission, her comrades helped her pack: water, two days’ worth of food, energy drinks, hand warmers, ammunition, spare thermal underwear, two pairs of gloves, and five pairs of socks, to be changed frequently to protect her feet from the severe cold. Anna also packed a compact mirror and some foundation. Her comrades joked that it felt like preparing for a wedding.

“The bride’s morning,” teased “Shtopor,” who was heading out to the positions with Anna.

“The bride” laughs, hiding her face behind the plates of her bulletproof vest like a veil. But in an instant, she composes herself. The group was scheduled to move to the starting point at 3:30 a.m., yet they had to wait until morning because of a difficult situation on this section of the front. The Russians were launching an attack, trying to cut Ukrainian supply lines and gain advantageous positions.

Anna covers 15 kilometers on foot in a day. She passes through ravaged villages, where no one remains. As darkness falls, she reports over the radio: “Reached the position.” Two weeks lie ahead, pressed close to the enemy, where survival depends on skill, strength – and luck.

Text: Diana Deliurman

Photos: Nadiia Karpova, Diana Deliurman

Adapted: Irena Zaburanna